...we went ahead and got a puppy. Bernie is 4 lbs. 10 oz., part Shi Tzu and part Yorkipoo -- hypoallergenic and non-shedding -- our own designer lap dog. Now if they could only design one that won't poop on the designer carpet. Other than that, he's charming and congenial enough. The tail does wag the dog in this case. I grew up with dogs. Can't remember ever being without one, sometimes two, until my last year in high school when Skip wandered off and we found him dead on a country road, victim of a passing car, and we never replaced him. Our dogs were mongrels many times over, bred by a casual encounter in a vacant lot. In our small town we had no leash laws and no fences, and you would never pay mega-bucks for a dog as you could always get one from someone who handed you an extra pup, whether you wanted it or not. If you said no thanks as you couldn't take another dog right now, you might get a scowl and something about how you'd better take it, seeing it was likely your dog that knocked up theirs. Our dogs were free roamers, and the house was clearly "no trespassing." They had normal dog names like "Spike" and "Chase," not "Wilson" or "Hollingsworth." When we heard something like "our dog is really a member of our family" or "he's our baby," we'd roll our eyes at the anthropomorphisms -- the ridiculousness of some people who couldn't distinguish between man and beast. And now that my family has our own hybrid puppy, a part of me still feels the same way. Little Bernie is darling and affectionate and entertaining, but if he ever becomes my "best friend," someone please send me to the shrink. On the other hand, I do find myself talking to him sometimes as if he's human, and he does seem to know when we're talking about him, cocking his head a little with curious, baited breath. My daughter is making him a Valentine's card. Cute, but I did draw the line at the suggestion we get him a Seahawks T-shirt. What is the impulse that drives us to imbue a dog with human characteristics with terms like "naughty" or "neurotic" or "baby" or the name "Bernie" (officially Bernard Lee Petersen)? On the other hand, why should a little anthropomorphizing bother me? I think both instincts are good ones. First, to draw the line between man and beast is to recognize our uniqueness and honor the created order. Keeping the distinction also acknowledges our first God-blessed mandate, a place of authority, which in part involves naming the animals, that is, affirming their dignity as God's creatures. It means investing a personal interest in them and celebrating each animal's distinguishing traits and their unique place in God's world. We're also given the responsibility to care for them and protect their well-being and survival, tasks often referred to as "stewardship." Taking a dog, as well as our long-term resident blind hamster, into our home reminds us of the God-given relationship we have with animals. By extension, our dog also connects us to the rest of creation by getting us outdoors more often -- to walk, run, smell the air, and watch for what he might be rooting up in the dirt. Having animals to attend to and be attended by helps soften a paved-over and increasingly digitized world. Our dog earns his keep by drawing us back to creation and the Creator. But what impulse drives us, even from our youth, to lend human traits to animals? Are we so ego-centric that we can't help imagining an animal as one of us? Well... yes, it seems so. Stories and fantasies, in oral and written traditions, abound with animals that possess distinct personalities, characters capable of thinking, feeling, and talking like humans, portraying our most heroic and nefarious inclinations. As projections of our imaginations somehow these animal characters help us understand ourselves and our world more fully. These portrayals also bond us more closely to our fellow non-human creatures. Reading stories like Aesop's Fables or Charlotte's Web can cultivate empathy and compassion even for a spider. After reading Watership Down, I'll never be able to see rabbits without thinking about social conflicts - theirs and ours. After such immersions of the imagination, it's impossible to look at animals purely with the distant, scientific gaze of objectivity. And after having an animal live with us, it's easy to start seeing some similarities. We realize the distance between us and animals is not as great as we may have once assumed. The result is we become more respectful and loving of animals. So, my rational mind helps keep me and beast in our distinct and rightful places, and my imagination helps me love them as I ought. I'm thankful my kids have an opportunity to grow up with a dog. Besides the entertainment and responsibility Bernie brings to our home, he also keeps us mindful that we and the animals are really integral to each other's kingdoms, all of which is God's kingdom. My only concern is that my six-year-old is starting to take on the personality (canine-ality?) of the dog.

0 Comments

January, 2015

I was listening to CBC-AM on my way home the other day, and over the air waves this hit me: We have advanced from canoes to galleys to steamships to space shuttles. We are more powerful than ever before but with little idea what to do with all that power. We are accountable to no one. We are consequently wreaking havoc on our fellow animals and on the surrounding ecosystem, seeking little more than our own comfort and amusement yet never finding satisfaction. Is there anything more dangerous than dissatisfied and irresponsible gods who don't know what they want? Yval Noah Harari (commenting on his book, Homo Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind.) If a statement like that doesn't throw you back, few things will. Hearing this honestly made me tighten my grip on the steering wheel in holy terror. I wondered how much I've bought into this line of thinking that we're "advancing" as a people without any moral principles to guide us other than "we can do it, so it must be fine." Are we as a human race too drunk on the possibilities of our own power to give a dam about the consequences of our choices for ourselves and the world? Or is it simply that we can't do anything to stop it, so we may as well hang on for the ride? And if we question such "progress" and our perpetual running after "comforts and amusements," by what authority do we do so? With increasing capabilities easily comes the belief that we are gods and can therefore make our own judgements of right and wrong. Democracy doesn't help much because our decisions come simply from a consortium of gods, decisions which may change with the winds of place and time. The conundrum screams for some guidance from outside of ourselves. As recently as the Middle Ages, theology used to be the pinnacle of human inquiry. The desire for God and understanding his ways was considered both the sail we held up for divine power and the rudder that kept our ship on a true course. And as we became aware of what was possible when we were untethered from these theological moorings, humans gradually supplanted God as the centre of the universe. We became the universe's sole guardians and arbiters of its use. But we have repeatedly shown that we are discontent with this new arrangement. We are restless, never feeling we have achieved our utopia. Even those of us who claim to be happy with our lives--our new homes with central air, new SUV's and low gas prices, new updated versions of smart phones, or new light-weight bicycle we use to defy the onslaught of human progress--when asked about the ultimate purpose of it all, sit somewhat stunned, babbling only half-baked answers. Our minds are not trained to think theologically because we've taken God out of the picture. Harari eloquently states a legitimate fear we should all be confronting: "Is there anything more dangerous than dissatisfied and irresponsible gods who don't know what they want?" We need to put theology front and centre again. This doesn't mean we all need to go back and get another degree (although I found it can't hurt). It simply means we need to start asking, regularly, the right questions: If there is a God, who is he or she? What does he want with this world and the human race that seems to be restlessly running it on their own? What do we want with God? How can he answer our deepest desires for happiness, love, justice, peace? Until we get back to pursuing God, we'll never be satisfied pursuing anything else and we'll never have an answer to Harari's heart-stopping proposition. The other night, my six-year-old suggested for her bedtime story that Santa go to church. I cleared my throat and took a deep breath for some inspiration, and tried a story on the requested theme. Here's a more polished version of our story that night...

One year, Santa had to stay for breakfast Christmas morning because he couldn't get back up the chimney. When Kaitlyn came downstairs rubbing the sleep out of her eyes, she found him half-way up the chimney with his bum sticking out of the fireplace. She pulled and pulled until Santa popped out. When Mom came downstairs and saw Santa sitting dirty and exhausted by the fireplace, she said "Oh dear." "Your chimney's a little too small," Santa said. "And you're a little too big," Kaitlyn laughed. "Yes," he said sadly, "you're right. Too many cookies." "You poor thing," Mom said, and while they were on the topic of food, she added, "Why don't you stay for waffles and bacon?" "Well, I am feeling a little peckish for something more wholesome than cookies." So Santa stayed. Kaitlyn and Karis showed him all their toys, which Santa had delivered the last couple of Christmases: little stuffed animals, a snow globe, a flashlight... Santa yawned but tried to look interested. "Oh, yes, I remember those," he lied. Dad came trundling down the stairs in his pajamas whistling "We Wish You a Merry Christmas" just as Karis announced, "Dad, Santa's staying for breakfast!" "Oh brother, what now?" Dad said. "He got stuck in the chimney because he ate too many cookies," Kaitlyn said, "and I pulled him out!" Soon waffles and bacon were being passed around the table, the syrup was poured, and lips were smacking. "Do you suppose I could have one more of those," said Santa, licking a finger. In fact, he said it nine times, and after his tenth waffle he let out a loud burp, rubbed his stomach and groaned. "Sorry, bad vice. And if I'm not careful, the vice might put a grip on my heart." And he tried to laugh, but instead of coming out "ho, ho, ho" it came out "he, he, he." "What does vice mean?" Kaitlyn whispered to her dad. "Bad habit," Dad whispered back. Then Kaitlyn saw a tear come to Santa's right eye. "I know I eat too much," he said. "'More' is my middle name, I'm afraid. Santa More and More Claus." Mom cleared the table of left-over waffles and bacon before Santa could take another bite. The family hurried to get ready for the Christmas morning church service, except for Kaitlyn, who stayed talking to Santa. "Why don't you just eat one or two then instead of ten?" Kaitlyn asked. "Oh, I could never eat just one or two. If I did that, there would eventually be no more Santa, and no one would ever stand for that. You see, if you take the "More and More" out of Santa Claus, you have nothing left -- no Santa and no dolls, no bikes, no TV's or anything-- except for maybe one or two things you get from your parents." "That reminds me," Kaitlyn said. "I lost my Barbie you got me last Christmas and now I only have eleven left. Could you get me another one?" "Yes," Santa said with a big sigh as if the weight of the whole world were on his shoulders, "I suppose." There was a long pause, and then Kaitlyn said, "Do you have any kids?" "Oh, no," said Santa. "I'm just too busy with all the kids of the world. But I don't often have waffles and bacon with any of them." He smiled at Kaitlyn as if he'd met a long lost friend. Mom, Dad, and Karis appeared, dressed for church. "Can Santa come to church with us?" Kaitlyn asked. "You'd better ask him if he wants to," Mom said. "That would be marvelous," Santa said. "Never been to church before." Santa insisted he drive them all to church with his sleigh and eight reindeer. So the family piled in with Kaitlyn and Karis sitting on the seat beside Santa, and Mom and Dad sitting atop his enormous pile of presents and hanging on for dear life as they lifted off into the sky. At church, Santa attracted lots of attention, of course, and all the kids had to touch him and say "hi" and tell him "merry Christmas" with big smiles. Some even gave him candy canes. Santa had never felt so loved. They sang "Joy to the World." The pastor told the Christmas story about when Jesus was born and the poor shepherds saw him first and then ran all over town telling everyone. He said how Jesus was the best gift ever because he was God's love to the whole world, and that was all anyone really needs. At this, Santa's ears pricked up, and with a very calm smile on his face he let out a long sigh. This time it was not the weight of the world ON his shoulders that he felt but the weight of the world falling OFF his shoulders that he felt. After the church service, Santa gave Kaitlyn a big hug. He said, "You gave me the best gift ever, better than any gift I've ever taken down any chimney. My middle name won't be 'More' anymore. It will be 'Enough,' Santa Enough Claus." Kaitlyn laughed. "Can I come visit again next Christmas?" Santa asked. Kaitlyn glanced at Dad who smiled and nodded "yes." Santa jumped onto his waiting sleigh. He waved good-bye, and as Kaitlyn watched him go into the sky, she noticed lots of boxes and bows falling from Santa's sleigh like rain all over Vancouver until his sleigh had less and less and was finally completely empty. As he went, everyone heard him howling louder than they'd ever heard before, "Merry Christmas, everyone! Ho, ho, ho!" I've noticed a recurring theme in church recently coming from our pastors: all of life is a sacrament. Hearing this blesses like fresh water. And it reaffirms one of my greatest takeaways from my studies at Regent College: a sacramental view of life.

If you have a church background, you were taught that there are either seven sacraments (Catholic) or two (Protestant). These are sacraments the church has formalized, and I'm thankful for them. But deeply imbedded in Christian orthodoxy, I believe, is the belief that all life is sacred (belonging to God) and therefore should be lived sacramentally. So what does this lofty statement mean? I understand "sacrament" as a thing or an event that helps us in two ways. First, sacraments help us understand God and how he engages with us and the world. If God made the world, it reveals something of himself. If God made us in his likeness, we can learn something of God from looking at ourselves (both what he is and what he is not). Just as viewing an artist's work tells us about the artists, so studying the world tells us something about the Creator. Secondly, a sacrament invites us to participate in God's life and death. If you've been reading my blog posts, you will have noticed various examples how I view all of life as a sacrament: a tree in the back yard, morning sunlight in the park, a song, a book, pigeons mating, things kids say, smart phones, and even mass killings. But wait, you say, how on earth can you see bad things as sacraments? Are you some kind of sadistic nut job? Surely this is heresy. But let's not forget the church's highest sacrament, The Lords Supper, celebrates the worst of all events, the death of Christ, which is also the best of all events. Within the bad events of our world, like mass killings, is Jesus' own death because God suffers with and for the victims of these tragedies and also the perpetrators. These horrible events should remind us that God does not divorce himself from suffering and death but rather he absorbs in his own suffering the evil of the world. And, these events call us to participate in this same suffering by our compassion, our outrage, and also our confession. Do these kinds events bring us to our knees in grief over our own acts of hatred? Do they cause us to combat evil? Do they move us to care for the suffering? Yes, even bad things can be sacraments which draw us to participate in the life of God. Some church liturgies use the phrase, "the gifts of God for the people of God," when serving the bread and wine for The Lord's Supper. Essentially, this is where sacramental living starts: a sacrament is a gift by which we commune with God. We receive the gift of God in his son -- in his life and his death. Jesus' life among us affirms Gods total involvement in our world. He's in, with both feet and with every fiber of his being -- loving it, celebrating it, struggling with it, dying with it, and resurrecting it. His sacrament is an invitation, every day and in all things, to participate in his life. October, 2014

In observation of Thanksgiving Day, I thought I'd re-post this with minor revisions... My daughter brought home from kindergarten the announcement that her class was doing "gratefulness circles" and she thought she'd reproduce the idea around our dinner table by directing each of us to name what we were grateful for. I have to admit, I had to search for a few embarrassing seconds. It didn't come automatically. My parents could be right. Maybe my generation really is spoiled. But every generation thinks the one coming after it is "spoiled." The folks of my father's generation, who went through the Great Depression, and in some cases lost whatever they had, thought my generation didn't know how to go without. Some call the Millennial Generation the "entitled generation," i.e. feeling deserving of what they want. Blame it on too much of a good thing, too much automation, or the basic decay of human character. We could all wear the label "dissatisfied and entitled" at our worst moments. We want what we want without delay. A recent report from researchers studying the effects of gratefulness should give us pause. The study found, not surprisingly, that those who were more grateful experienced less stress, less anger, and more satisfaction in life. Then why don't we practice gratefulness more often? Why is it so difficult to simply say, "Thank you" and really mean it? Possibly the most basic reason is that gratefulness implies a transaction between two people, but we don't feel we really owe anyone our thanks. We have fewer and fewer relationships in which such a transaction where giving, receiving, and thanking is necessary. We are caught in the illusion that we don't need anyone else, we can make our own way, so we have no one to thank. Think of your daily activities. One could potentially go days, weeks, or months without any personal transactions, and sadly some do. Automated checkout's substitute for real people everywhere. The person is removed to a remote and obscure accounting office, where lists of transactions flicker across computer screens. Gratefulness implies connections to a giver. Gratefulness circles, as my daughter engaged in at school, are a great start, but to simply say "I'm grateful for X" without addressing that thanks to someone is simply a self-enrichment gimmick. It's not real. If I say, "I'm grateful for my health, or my home, or a beautiful environment, or my job, or my family" I'm only half way there. Who am I thanking? Myself? The thought should be self-evidently ludicrous. And thanking good fortune or the universe defies the logic of the words, "thank you." Who's "you"? Gratitude by definition requires a giver and a recipient. If we cannot acknowledge a giver, our thanks are turned inward and our gratefulness is virtually meaningless. Some of the most beautiful words from my kids are, "Thank you, daddy," because it means we're connecting and creating bonds. They're getting it: giving and receiving and the acknowledgement. Gratefulness is a most basic human sentiment and, as even the research indicates, it is one of our most healthy virtues. The beautiful thing is that gratitude breeds giving. Those who are most grateful are often also the most giving. This is the real "circle of gratefulness." But, you might say, what about people who have nothing to be grateful for? This is a legitimate question for people suffering crises and great loss. The surprising truth, however, is that these people are often the ones who most discover gratefulness in their lives. They have gained a great wisdom: the ultimate failure of self-reliance and the need to rely on another, and the inadequacy of possessions to fulfill us compared to the sufficiency of God. Yes, some curse God for their state in life and fall into despair and resentment, but many recognize whatever evil that has brought them to where they are is not from God, and rather that God is their only lasting solace, and for that they are grateful. To me, gratefulness has been one of the strongest arguments for the existence of God, and the reality of gratefulness is one reason I cannot conceive of a world without a personal God. And a tacit acceptance of God as some impersonal "force" or internal "feeling" or "idea" is not enough simply because a force cannot give me anything or receive my thanks. Gratefulness is embedded in our created-ness, and a personal relationship with our Creator is the core of faith and life. From the beginning, God has been The Giver and Source of all things by establishing creation with all its laws and wonders. And placing himself in the middle of his creation is his greatest gift of all. So the "you" of thanks is very near! Be grateful, yes. Then let's take the next step, and give thanks. September, 2014

Why is simple so difficult? While we spend enormous efforts to simplify our lives, simplicity seems forever to elude us. We find new ways of doing the same things because we assume the new ways will make our lives easier. We want to accomplish more in less time, giving ourselves more money and more free time. Then we spend our new free time frenetically searching for new ways to nullify the old ways and make life, we suppose, easier. No doubt, new ways may gain us more money and ease of living. But then, of course, new problems raise their ugly heads with each new device: How do we secure our "advances" and how do we manage it all and keep it all working! No worries, we've got a whole raft of therapists and medications that can deal with our anxiety disorders. The myth of "more choices makes us happier" only amplifies the difficulty of simplicity. Do I want my latte regular or skinny, caf or decaf, foam or no, what size? Do I want my carwash with no touch or soft touch? And do I want my undercarriage washed? Well who doesn't? Even those who have deliberately chosen a simpler life with less report at times driving themselves crazy with anxiety, obsessing about whether or not to purchase an item and what to throw away. I've come to believe that our human tendency, unwitting as it may be, is not to simplify but to complicate life. My daughter recently announced we had "only twelve" Barbies in the house. Are we actually running away from simplicity rather than toward it? And if so, is there any way to embrace simplicity and free ourselves from the anxiety of the growing snowball? This summer I and my family visited my wife's parents in Manitou, Manitoba. The name itself is like a mantra that lulls you into a sense of ease. Manitou Manitoba... I said it over a few times as we drove past wheat fields bending in the wind, letting the name roll languidly off my tongue. Manitou has about 900 people and no espresso bars or malls within miles. (Where does one get his morning fix in this place on his way to another frenetic day?) You can't be a stranger here. People really notice you and say "hi." They trust each other enough to leave their cars running while they go into the store to buy groceries. Kids wander the neighborhood on their bikes till they find other kids to play with. Who needs to arrange a play date? Our girls found two of my wife's old tricycles (remember those?) and scooted off, seeming to understand intuitively the absence of danger and a sense of freedom. Between the homes lie massive gardens. I watched as goldfinches landed on spikes of blooms, bending them as they gleaned seeds. Fifteen minutes passed seemingly in seconds. I watched wheat fields surrender to the wind, and I felt myself surrender to God, my soul expanding with the great breadth of the prairie. The views are unbroken by city high rises. (My gosh, they're hardly broken by a tree!) Like many, I've assumed Vancouver was the place to expand a person's vision beyond that of parochial villages like this one. But the reverse was true. The sweeping spaces drew my vision beyond my anxious little niche back home. The quiet and the scarcity of human life was initially frightening, but as I settled into it, the simplicity of the place lured me. My wife's parents are the most genuine, generous, salt of the earth people you'd ever hope to meet. I love them for how unquestioningly they've taken me in as one of their own. They have focused their lives on people rather than things. Except for books. My father-in-law, like me, loves books. But I think he loves people more. He's devoted his life to teaching, my mother-in-law to raising eight kids and twenty-one grandkids, and both of them to their community. Meal times with great home cooking are highlights of the day, accompanied by long chats, stories, and laughs around the table. They exemplify a simple life. But, you might argue, there aren't many distractions in a small town, so it's easy to live simply. Ask those who live there. They'll tell you even in a small town it's easy to get wrapped up in a complicated life. Well, you may say, they had to live simply with that many kids and on a teacher's salary. True, but they chose that life when they were fully capable of a more complicated life pursuing wealth. But why? They obviously love their lives and the people in them more than almost anyone I've met does. They're the people I think of when I hear Jesus' words: "The meek shall inherit the earth." It's not first of all the life of simplicity they've chosen. It's the Jesus of the gospels they've chosen. It's obvious they've caught what Jesus meant when he called people to a rest and simplicity that only God can give. They embody the kind of faith Jesus was on about when he pointed to the birds of the air and the flowers of the field to understand what it means to trust God without fear of tomorrow. My visit to Manitou called me back to Jesus: "Come to me, all you who are weary and burdened, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you and learn from me, for I am gentle and humble in heart, and you will find rest for your souls. For my yoke is easy and my burden is light." All Jesus wants is for me to partner with him, and other matters like lifestyle choices will fall in place. What a relief from a world that insists on easier and happier lives by finding new yokes to burden ourselves with, only to find that the substitute yokes are as oppressive as the ones we left behind! So, I've gathered then - from the prairies, the goldfinches, my wife's parents, and Jesus' words - that the ultimate answer is not only striving for a simpler life but letting God fill me, trusting that he'll supply every need. The simpler, more anxiety-free life will then be easier to adopt. August, 2014

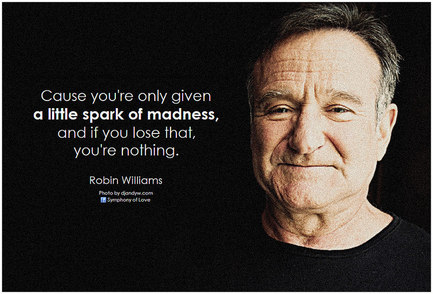

To say that "I'll miss Robin Williams" is perhaps a bit presumptuous since I never knew him. I did meet him once, very briefly, and his taking the time to shake my hand and exchange a few words left a big impression on me. I caught a glimpse of the humble, gentle, and generous soul his friends describe him as, a soul which is obvious in his films and monologues, too. See Patch Adams, The Birdcage, or The Fisher King as examples. His best performances left you with the sense that he understood the sufferings of the marginalized. Maybe this is why I miss him already: knowing I'll never see another of his honest, empathic performances again, ones that convince you, "Yeah, he understands and he cares." In my exchange with him I think I also caught a glimpse of the cloud that haunted Robin Williams much of his life. If you've ever struggled with depression, you can recognize it: glazed, slightly withdrawn, wanting like hell to engage as a real human being, but also wanting to run and hide. Maybe this is why I'll miss him. We had something in common. Robin William's depression, by his own estimation, was rooted at least partly in his relationship with his father. His dad was severe and sometimes belligerent. He felt alienated from the kind of loving father he longed for. Robin's own love for kids is a counterpoint to that experience. Interestingly enough, his mentor and comedy idol, the brilliant Jonathan Winters, shares a similar story. Obviously, wounds recognize their kin. But William's experience of alienation from a father's love was also the crucible for his amazing work. Humor comes out of pain. And he welcomed us into his and said in effect, "This is where we all meet as equals. We are all wounded travelers on a common shore searching for love. Let's laugh at the pain for awhile and love each other." His humor was a generous gift. I usually came away from his films not only refreshed but also a bit wiser and more ready to live. His talent was rare. There was not only empathy in his humor but also understanding and intelligence about the human condition. Flashes of revelation filled his best work. This is perhaps the greatest reason I'll miss Robin Williams. His revelations were compassionate and grace-filled. Even William's most confrontational humor was the kind of severe grace one needs to be shaken out of a malaise. His revelations were the beginning of hope because they reminded you, first, that no matter what you were not alone. It meant that he understood you, and the many who laughed understood each other. This is the beginning of healing and transformation, that is, by first seeing ourselves for who we truly are--broken and flawed humanity. Robin Williams helped us "seize the day." He gave us his broken self in myriad acts of grace and redemption. July, 2014

Every generation thinks the one coming after it is "spoiled." The folks of my father's generation, who went through the Great Depression, and in some cases lost whatever they had, thought my generation didn't know how to go without. Some call the Millennial Generation the "entitled generation," i.e. feeling deserving of what they want. Blame it on too much of a good thing, too much automation, or the basic decay of human character. We could all wear the label "dissatisfied and entitled" at our worst moments. We want what we want without delay. My daughter brought home from kindergarten the announcement that her class was doing "gratefulness circles" and she directed each of us around the dinner table to name what we were grateful for. I have to admit, I had to search for a few embarrassing seconds. It didn't come automatically. A recent report from researchers studying the effects of gratefulness in people's lives, not surprisingly, found those who were more grateful experienced less stress, less anger, and more satisfaction in life. Then why don't we practice gratefulness more often? Why is it so difficult to simply say, "Thank you" and really mean it? Gratefulness implies a transaction between two people. But more and more, we have fewer and fewer relationships where we feel such a transaction is necessary. We are increasingly caught in the illusion we can live and act independently, make our own way, and we have no one to thank because we can take care of ourselves. Think of your daily activities. One could potentially go days, weeks, or months without any personal transactions, and sadly some do. Automated checkout's substitute for real people everywhere. The person is removed to a remote and obscure accounting office, where lists of transactions flicker across computer screens. Gratefulness implies connections to a giver. Gratefulness circles, as my daughter engaged in at school, are a great start, but to simply say "I'm grateful for X" without addressing that thanks to anyone is simply a self-enrichment gimmick. It's not real. If I say, "I'm grateful for my health, or my home, or a beautiful environment, or my job, or my family" I'm only half way there. Who am I thanking? Myself? The thought should be self-evidently ludicrous. And thanking good fortune or the universe defies the logic of the words, "thank you." Who's "you"? Gratitude by definition requires a recipient. If we cannot acknowledge a giver, our thanks are turned inward and our gratefulness is virtually meaningless. Some of the most beautiful words from my kids are, "Thank you, daddy," because it means they're getting it. They know how it works: giving and receiving and the acknowledgement. Gratefulness is a most basic human sentiment and, as even the research indicates, it is one of our most healthy virtues. The beautiful thing is that gratitude breeds giving. Those who are most grateful are often also the most giving. Thus, the "circle of gratefulness" is complete. But, you might say, what about people who have nothing to be grateful for? This question is understandable for people suffering crises and great loss. The surprising truth, however, is that these people are often the ones who most discover gratefulness in their lives, and many discover that they have no one to thank, least of all themselves, for their lives, but they thank God. How odd, eh? Yes, some curse God for their state in life, but many recognize whatever evil that has brought them to where they are is not from God, and rather that God is their only solace, and for that they are grateful. To me, gratefulness has been one of the strongest arguments for the existence of God, and the reality of gratefulness is one reason I cannot conceive of a world without a personal God. A tacit acceptance of God as some impersonal "force" or internal "feeling" or "idea" is not enough because a force cannot give me anything or receive my thanks. Gratefulness is embedded in our created-ness, and a personal relationship with our Creator is the core of faith and life. From the beginning, God has been The Giver and Source of all things by establishing creation with all its laws and wonders. And placing himself in the middle of his creation is his greatest gift of all. So the "you" of thanks is very near. Be grateful, yes, and give thanks.  June, 2014 Sunlight filters through the kitchen Saturday morning as Diane and I clean up after last night's foray of getting kids fed and put to bed before we ourselves crashed. The kids (blessed, blissful relief) are sleeping in. A rare moment of togetherness for me and Diane, albeit amidst the ruins of dishes, macaroni stuck to everything, and clothes strewn across the floor. The coffee maker gives a few guttural coughs. Our first cup is ready. I glance at Diane, barefoot in capri pants and a loose blouse, and am taken back to my first attraction to her. On the radio come John Legend's romantic strains, "You're my end and my beginning" -- what a statement of love and devotion. I pause. "Diane, am I your end and your beginning?" "No," she says, flatly and unfiltered. "Good answer," I say. She's thinking what I'm thinking: How foolish to make such a pronouncement to anyone, especially if you've known them for any length of time. We've been married long enough to know that neither of us is deserving of such praise. That could only belong to... well, God. In fact, the line "You're my end and my beginning" sounds very biblical. In the final book of the Bible, Revelation, we find this statement ascribed to God three times, "I am the alpha and omega, the beginning and the end." The line from John Legend's song is also vaguely reminiscent of another line by T.S. Eliot's in his poem, "East Coker" (the 2nd of Four Quartets). The poem opens, "In my beginning is my end" and concludes several verses later with "In my end is my beginning." Between those two lines Eliot shows that intrinsic to every life is suffering, deterioration, and death. Even as life begins it is destined also to die. And near the end of his poem is a reference to Christ's death: "In spite of that [suffering and death], we call this Friday good." He's speaking, of course, about Good Friday. T. S. Eliot reminds me I need to acknowledge my flawed, mortal nature (which is my confession) and more importantly run to embrace Christ's mortality (which is my absolution). Only then can I expect to find any relief or restoration. So, Eliot counters John Legend's proposition that another human being can be our end and our beginning. That honor is ultimately Christ's. He is where it all ends and all begins. He is where we as self-sufficient beings end and also where we begin anew as loved by Christ. Another line in the John Legend song goes, "All of me loves all of you, love your curves and all your edges, all your perfect imperfections." Again, an amazing statement, but again misdirected if not directed to Christ. Most of us, after a short time in any relationship, understand these words for what they are -- infatuation borne on naive utterances. In truth, we can't accept much less endure these edges and imperfections in each other as we once may have. They grate on us. They make us turn the other way. They turn us into cruel, unforgiving jerks. In a moment of grace we may recognize our own imperfections as equally repulsive, and then perhaps begin to love the only "perfect imperfections" worthy of our devotion, Christ's own, because they are the ones that can truly complete us. I walk up behind Diane and put my arms around her, grateful for this gift of a woman, wanting us to love each other in spite of and because of our flaws and imperfections. She turns to return my embrace just as our toddler's voice calls down from upstairs, "I need my bum wiped!" Right. Accepting our messes and embracing Christ's extends also to our children. I sigh. In my mind I'm rephrasing Eliot, "In my toddler's end is my beginning" every morning.  May, 2014 This Monday is Memorial Day where I'm from in the States - sort of like Canada's Remembrance Day. It reminds me I've been remembering a lot lately. Not, as the day intends, remembering the many fallen soldiers - I don't really know any - but remembering my lost self. Before you assume I'm battling senility, hear me out. First, I got thinking about the word itself: remember. "Re-" referring to "dong something again, and "member" referring to members of a group or, as we usually think of it, pieces of data. At one level, remembering is about reassembling in our minds the various parts of a moment in time. But beyond this and maybe more importantly, by re-membering, when it's done well, we are putting together the pieces of who we are. Anyone who's looked closely through photographs of his or her early years knows that a series of photos is much more than a ticker tape of factual data. The photos are entries into a life, and by putting the pieces of our lives together, we are re-membering our selves, creating our stories. And, as we view those photos, if we are sitting next to a family member who has shared those same moments, we know that their stories of us get added to ours, or perhaps we discount them entirely, as we shape our deeply textured narratives. If you haven't re-collected your old photos recently and slowly re-collected the parts of yourself you've lost, putting them together into a bigger picture may bring more benefits than you would have thought possible. If you haven't kept your old photos, some solitude and reflection can initiate the same process. To my pleasant surprise, my kids have served as a trigger for a lot of re-membering of my self lately. By attending to their world and their concerns, my two girls (5 & 3) have helped me relive my own childhood, bringing to mind many occasions, along with a flood of attendant feelings and impressions: the smell of a kindergarten classroom, the elation of riding solo on my bicycle for the first time, the cold in my hands after building a snowman, dandelion chains and the stains they left on my hands, the death of my first goldfish and the questions: Why isn't she swimming, Dad? Such re-membering has made me deeply grateful, grounded, and whole. If re-membering really is a meaningful process for individuals, why not also for community gatherings, such as Memorial Day gatherings or church gatherings? These are occasions for re-membering the community, bringing the members together again, retelling our common story, filling in the holes, and mending the broken places. The church communion service, sometimes called a remembrance feast, is the ultimate occasion through the bread and the wine for re-membering ourselves one to another and to God. The bread, Christ's body, broken and divided among us for the purpose of putting us back together - an amazing mystery! The benefits of re-membering being obvious, the process can nevertheless be a scary undertaking. (In fact, you might feel like an undertaker exhuming a past you thought you'd put to rest.) We open ourselves to a gamut of emotions when we relive our past, sometimes nostalgic, happy ones, but sometimes broken ones with lots of scattered pieces we'd rather leave in the bottom of the closet. Re-membering may prompt us to look for someone to go through the process with us, and I think this is a good impulse. I've been a happy recipient of such re-membering, attended by an insightful and caring friend. For me, re-membering would not be complete if God were not there as the ultimate attendant, mender, and story creator. Welcoming him into the process as I would a trusted friend is the ultimate re-membering. I have started with a simple prayer, "God, you're welcome here. Please help me put the pieces back together." And when we discover ourselves mending and becoming whole, I believe, we have the beginnings of making healthy relationships. Knowing our own stories puts us in a confident place to look at the pictures from other people's lives, hear their stories, and help them re-member as well. |

Archives

January 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed